Research

I study civil wars, in particular how different forms of civilian collective action emerge and change the dynamics of war, and how (armed) conflicts evolve, escalate, and transform. This research lies at the intersection of international relations, comparative politics, and political sociology. I strive for an interdisciplinary approach and combine theoretical perspectives and methodological approaches from political science, sociology, history, and anthropology. I put particular emphasis on in-depth fieldwork and combine qualitative with quantitative research methods.

Projects

Countering Jihadi Insurgencies in Africa: Repress, Resist & Reorder (COUNTERRR) (2025-2030)

ERC Starting Grant funded by the European Research Council

COUNTERRR examines domestic responses to jihadist armed groups in Africa, analyzing variation in state repression, community resistance, and the evolution of security across Mali, Nigeria, and Mozambique. Violence by jihadist armed groups poses a distinct threat to social, political, and economic orders across Africa. This project focuses on how domestic actors—governments and affected communities—counter jihadist armed groups operating in three countries. The project explores why these domestic actors choose varied strategies—such as state repression, foreign intervention, nonviolent or violent community resistance—when countering jihadist threats and examines the effects of these strategies on conflict stabilization or escalation. The research methods will combine qualitative cross-country and subnational comparisons with extensive fieldwork in the project countries. Understanding how African countries and affected communities respond to jihadist insurgencies will help international actors to coordinate and adjust their responses to benefit from local knowledge and prevent further escalation of conflict.

GOV-JIHAD: Governing Jihad in Africa: Ideology, Political Economy, and Violence (2025-2028)

ORA8 Grant funded by UKRI, ANR, and DFG, together with Vincent Foucher, Eric Morier-Genoud, and Yvan Guichaoua

Since the collapse of the “Caliphate” of the Islamic State in the Levant, sub-Saharan Africa has been the next jihadist frontier, actively promoted as such by global jihadist networks. This armed challenge has largely been analysed from the perspective of “violent extremism,” suggesting that jihadist armed groups produce new forms of violence, mobilisation, and governance that threaten African states in new ways. However, it is far from clear that jihadist armed groups have had such a revolutionary effect on contemporary conflict dynamics. Some insist that jihadist violence is very much in line with earlier forms of conflict. What this project intends to do is unpack this assumption and we therefore ask: How (if at all) has jihadist ideology changed political, social, economic, and political dynamics across African conflicts? Current scholarship is ill-equipped to answer this question. First, the dominance of jihadist brutal violence in analyses prevents many from recognizing these groups as grounded social and political phenomena. Second, Africanists are divided over whether local roots of conflict matter more than transnational linkages for these conflicts—a debate that hinders our understanding of how the local and global interact. Third, prior country-specific work makes it hard to compare systematically and effectively across contexts and generalise findings. Lastly, research has been hampered by the lack of reliable information, which creates limited if not prejudiced analyses.

GOV-JIHAD innovates the field by understanding jihad as a social, economic, and political phenomenon and inquiring how jihad governs and is governed in three different realms: how ideology shapes what jihadi armed groups value and try to impose systemically (norms), how ideology and pragmatism shape how they generate and use resources (spatial expansion and political economy), and how ideology and tactical imperatives shape how they fight (and against whom) (violence and counter-violence). This analytical effort requires an approach that takes the local and global into account. GOV-JIHAD will form a team of researchers who will conduct joint fieldwork to facilitate meaningful and empirically informed comparisons. We will collect high-quality data through immersive fieldwork and archival work, using careful process tracing and systematic historical analysis to analyse how ideology shapes conflict in three main regions: Mali and the Sahel region, Nigeria, and Mozambique.

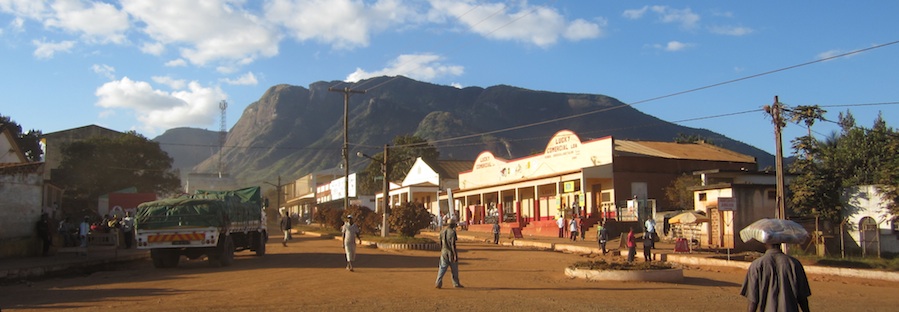

Violent Resistance: Militia Formation and Civil War in Mozambique

Book published in January 2022 with Cambridge University Press

Why do communities form militias to defend themselves against violence during civil war? Using original interviews with former combatants and civilians and archival material from extensive fieldwork in Mozambique, Corinna Jentzsch’s Violent Resistance explains the timing, location and process through which communities form militias. Jentzsch shows that local military stalemates characterized by ongoing violence allow civilians to form militias that fight alongside the government against rebels. Militias spread only to communities in which elites are relatively unified, preventing elites from coopting militias for private gains. Crucially, militias that build on preexisting social conventions are able to resonate with the people and empower them to regain agency over their lives. Jentzsch’s innovative study brings conceptual clarity to the militia phenomenon and helps us understand how wartime civilian agency, violent resistance, and the rise of third actors beyond governments and rebels affect the dynamics of civil war, on the African continent and beyond.

State-Militia Collaboration and Political Order in Civil War (2017-2021)

NWO Veni Project funded by the The Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research

Governments in Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan and Sudan have mobilized militias to defend the state and the local population against armed rebellion. The empowerment of such progovernment armed groups has varying consequences for security and political order in conflict-ridden states. Recent headlines like “Afghan Militia Leaders, Empowered by U.S. to Fight Taliban, Inspire Fear in Villages” (Goldstein 2015), “Power Failure in Iraq as Militias Outgun State” (Parker 2015), and “Chaos Grows in Darfur Conflict as Militias Turn on Government” (Lacey 2005) support the notion that empowering militias leads to disastrous outcomes. But contrary to what such war reports suggest, the disruption of political order and security by militias is not inevitable. In civil wars in Mozambique, Peru and even Afghanistan, many militias neither mounted a serious challenge to state power, nor threatened the population. Instead, they allowed the state to restore order and security. Under what conditions does state-militia collaboration sustain or disrupt political order? More specifically, under what conditions do militias target state institutions and the local population or refrain from doing so? This project develops a new theory of the impact of state–militia collaboration on political order—the extent to which militias exercise state functions and perpetrate violence against the local population. It analyzes subnational variation of state–militia collaboration during the Mozambican civil war for the purpose of theory development and tests implications for the macro-level in a cross-national analysis of state–militia collaboration in recent African civil wars. By elucidating the ambivalent effects of state–militia collaboration in civil war, the research seeks to critically interrogate the assumptions informing current policy in contexts such as Iraq and Afghanistan. The findings will provide insights into how militias can be made more accountable to the state and the local population and less susceptible to co-optation by violent entrepreneurs.

The Evolution of Violence During Mozambique’s Civil War (1976-1992) (2016-2017)

Funded by the International Peace Research Association Foundation

Although the civil war in Mozambique (1976-1992) had important geopolitical implications and severe humanitarian consequences, its systematic study is relatively limited in comparison to other armed conflicts. One reason is the dearth of available data, in particular on the subnational level. Cutting-edge research of civil wars, however, requires fine-grained subnational data to uncover the microfoundations of insurgent mobilization, violence against civilians, rebel governance, and displacement. This project makes use of the author’s unique collection of primary documents from Mozambican archives to create a dataset of violent events during the Mozambican civil war to facilitate systematic analysis of variation in wartime violence across space and time. The project contributes to our understanding of the local dynamics of war in Mozambique and the causes and consequences of political violence more generally.